An Iranian-American Mother's Reckoning

Words by Shideh Etaat

As I’m writing this another revolution has erupted in Iran. Millions of unarmed civilians, the people the Lions—came to the streets demanding an end to the Islamic regime, and, there is no other way to put it, were massacred by their own government as a result. The U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) has verified 6,883 deaths and is currently investigating over 11,280 additional cases. Other reports from medical networks and international observers suggest the number could exceed 20,000 to 30,000. It is extremely difficult to get an exact number as an Internet blackout remains in place throughout the country.

These were old women with bloodied mouths screaming,

“I don’t care if I die! I’ve been dead for 47 years!”

Clerics cursing Khamenei and his murderous ways. Masked youth with peace signs and a blow torch lighting crooked cops on fire. A woman filming from her window up above. She yelled for the kid to run as the other crooked cops on their motorcycles chased him down.

“Ghorboonesh behram!” she shouted, a saying reserved usually for your own children, something along the lines of, I would die for you.

We saw the kid’s body as he ran for his life, the motorcycles so close to him. There was the sound of pop, and the video ending, and we didn’t know what happened right away, but also we knew exactly what happened.

We are seeing it as we scroll and watch videos that come in despite the Internet blackout—families desperately searching for the bodies of their loved ones thrown into the pile of black body bags. They unzip and they scream and they cry for their brothers and sons, sisters and daughters. We heard the most heartbreaking sound of an older man searching for his son amongst all the thousands of body bags.

“Sepehreh Baba. Sepehreh Baba. Dad’s Sepehr, God, where are you?” he pleaded, the ache in his voice, the hollowed out grief and shock, the courage to feel that we most associate with women is cracking open and softening the hearts of the men too. The collective wailing behind him a sound that felt primal, deeper than their vocal cords.

There the young dads, aspiring musicians, grandmothers, teenagers, poets, doctors, girls without hijab, lighting up cigarettes, burning a picture of the Ayatollah’s face with a fire they started all on their own.

On the streets some chanted, “Javid Shah!” which means long live the King!

As if going back is a possibility, as if 47 years of murderous oppression, economic crisis, and isolation—along with the stifling of any artistic or intelligent voice—was just a blip, and everything can go back to the way it was. A country dismantled, taken hostage by a weaponized form of religion, even if it is freed, is forever changed.

I keep thinking about this longing for return. My parents exile 43 years in the making, their memories so detailed and specific, a certain kind of holding on. My own instinctive desire for a homeland I’ve never witnessed—to be held by the land, by the people, the language, the food, and the sea.

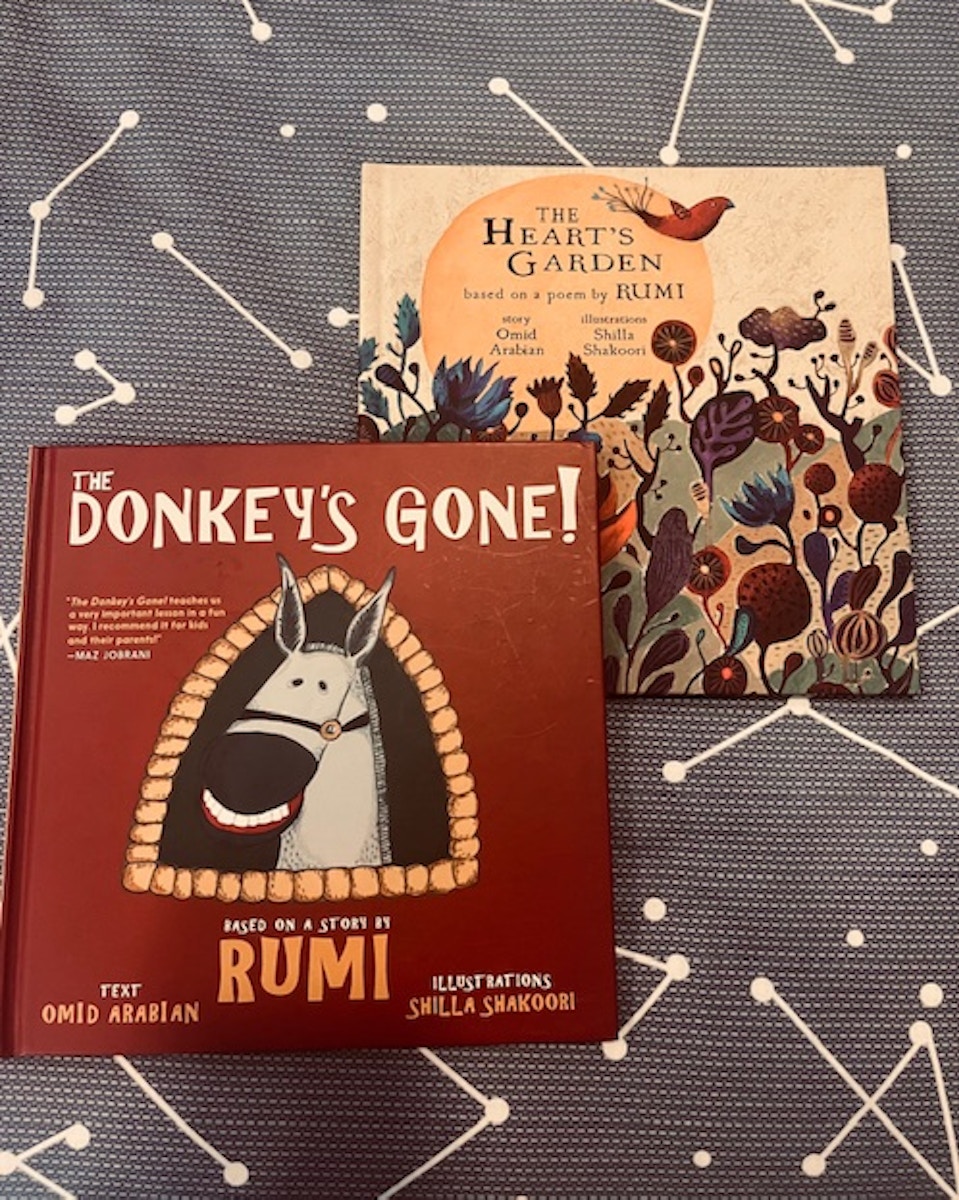

My daily quest to preserve Iran somehow for my seven-year-old son too. Speaking the language to him, making sure he’s in a school with a huge Iranian presence, the food we eat, jumping over the fire before Norooz, reading Rumi children’s books, telling him a kid-friendly version of what is happening there right now, even his name—Iman—is very Iranian. On purpose.

In the back of my mind is always this thought: If we can never get Iran back how do we make sure it stays inside of us, inside of our children too?

But the truth is that there is no getting anything back, no returning after so much time and loss, after all the wreckage and destruction, and after we have the courage to acknowledge our collective grief. There can only be the creation of something different: something new.

"I keep thinking about this longing for return. My parents exile 43 years in the making, their memories so detailed and specific, a certain kind of holding on. My own instinctive desire for a homeland I’ve never witnessed—to be held by the land, by the people, the language, the food, and the sea. "

Iran makes me think of my husband Elia’s brain. How eight years ago it was also jolted, uprooted, from its original state. A brain injury can look so many ways—his has forever altered his memory, his sense of self, his awareness and knowledge, his ability to communicate, walk, process, and how he navigates the world.

Over dumplings, the other day Elia sat across from me in his wheelchair. Our son next to me, my brother next to Elia. If I don’t make conversation, it’s hard for Elia to initiate himself.

“Things are getting crazy in Iran,” I told him.

“What?” he responded, which is his usual response after I tell him anything. As if he can’t hear me, but really it’s that his brain has a hard time processing the first time. I said it again. This man who once wore a T-shirt with Mossadegh’s face on it, who knew the history of Iran better than any average Iranian and some not average ones, who studied abroad in Turkey and tried to unsuccessfully weasel his way across the border. He said,

“It’s crazy. I don’t know why there’s no democracy yet,” which is actually a very wise thing to say. But then he jumped to, “Who’s taking me home? You’re Shideh? You’re my wife?”

Iman asked him what his favorite kind of dumpling was. Elia replied, “what’s your name, sir?” He was only half joking, I think. He forgets names easily. It’s not his fault, but also I felt so mad, I could scream.

“It’s Iman, Elia, you know that,” I said. Sometimes when I’m in it, I can try to make light of the situation. I can be a “higher self” version of me and flow, be kind and loving, but sometimes I zoom out and I can see just how shitty this all is, especially for Iman. In those moments, it breaks my heart every damn time.

When I took Iman to the bathroom I told him,

“Dada forgets my name sometimes too.”

“It doesn’t bother me,” he said, “he just needs a reminder.” Then he washed his hands like he was the wisest one of us all because for the most part he is.

“Yeah, that’s it,” I said, “his brain is hurt and he needs a reminder.”

How loving and understanding. With what kindness he sees his father. Maybe not always, but in that moment, yes.

He doesn’t know Elia any other way because I was pregnant with Iman when his dad got hurt. He lived it while inside of my body. There is no returning for Iman, and so many years post-injury there is also no returning for me or his father. There is only a new way forward. A way we are creating together, and in that moment, our child was leading the way.

Where did we put all our personal and collective grief over what’s happening abroad but also in this country? As humans it’s hard enough, as mothers sometimes it feels like an impossible feat, as an Iranian mother right now the task is even more overwhelming.

For one I’ve learned that obsessing over social media and being bombarded with information constantly isn’t healthy. The goal is to stay informed—no matter what your cause is—with compassion and empathy, while being careful not to burn out.

Because guess what? We need mothers—our wisdom, heart, and love. Our children need us, but so do our communities, our cities, and our countries.

What helps me navigate these seismic shifts is also making sure I find my light. We all have one inside of us: gifts, talents, and passions. Finding it and fanning the flames. No light is too small or too big. Maybe it’s mothering, creativity, or activism. Perhaps it’s protest, volunteering time to a worthy cause, or educating yourself beyond binary thinking.

Yesterday I took Iman to a protest in our neighborhood. We made our Free Iran sign and took my mother. He complained on the way there which he tends to do when he doesn’t exactly know what is about to happen. Can you blame him?

I assured him we would only stay for a little bit and for a solid 20 minutes he was chanting along with the slogans and was immersed in the crowd, watching the flags wave in the air, a displaced people come together and carry the spirit of hope.

It was a small tiny act, but it felt like some kind of light.

Shideh Etaat is a LA based mother and writer with roots in Iran. Her first novel Rana Joon and the One & Only Now was published in 2023. She is also founder of Aramesh Well Being where she does one-one life coaching and leads women’s groups with the intention of processing through writing and the magic of being witnessed.