How to Raise Politically Conscious Kids—Without Telling Them What to Think

Words by Deepti Sharma

Last year, my 9-year-old, Zubin was watching a YouTube video on how to solve a Rubik's Cube. (My kids are only allowed to watch YouTube on the TV, where I can see and hear what they're watching.) In the middle of the video, a political attack ad from the Cuomo campaign came on. I quickly changed it so he wouldn't hear it. I thought that was the end of it.

A few days later, it was mayoral primary day. Zubin knew that after school drop-off I was going to vote. Out of nowhere, he asked me, "Why are they calling Zohran bad?" I paused.

We ended up having a conversation about political ads. I didn't lecture him about what to think. Instead, I asked questions: “How does hearing this make you feel?" "How do you think we should think about supporting others?”

What stayed with me wasn't the content of my answer, but the realization that my children were already picking up on how power and prejudice show up together. Politics wasn't something happening "out there." It was already in our living room.

That became even clearer in the months that followed. We took our kids to Mamdani's inauguration, where they heard immigrant stories celebrated openly, alongside conversations about what it means to be a sanctuary city right now. Days later, on the way to school, they overheard NPR coverage about an ICE agent killing someone in Minneapolis. Suddenly, words like undocumented, ICE, and deportation weren't abstract. They were part of our daily family conversations.

This is where many parents find themselves stuck. We want to raise kids with strong values, but we don't want to indoctrinate them. We want to protect them, but we also want them to understand the world they're inheriting. We want them to think critically, but we also know that some things are simply right and wrong.

For me, those goals aren't in conflict. There are things that feel morally clear about dignity, harm, responsibility, and who deserves safety. I guide my kids with those values. At the same time, I don't want them to accept anything at face value, even when it's something I believe deeply. I want them to understand why values matter, not just repeat conclusions.

I was raised in Queens, and now I'm raising my kids here. Queens is a place where civic life happens in public—on sidewalks, at school drop-offs, and in community centers. Growing up, I learned early that politics wasn't reserved for television debates or Election Day. It showed up in who had access, who was protected, and who was asked to wait.

"This is where many parents find themselves stuck. We want to raise kids with strong values, but we don't want to indoctrinate them. We want to protect them, but we also want them to understand the world they're inheriting. We want them to think critically, but we also know that some things are simply right and wrong."

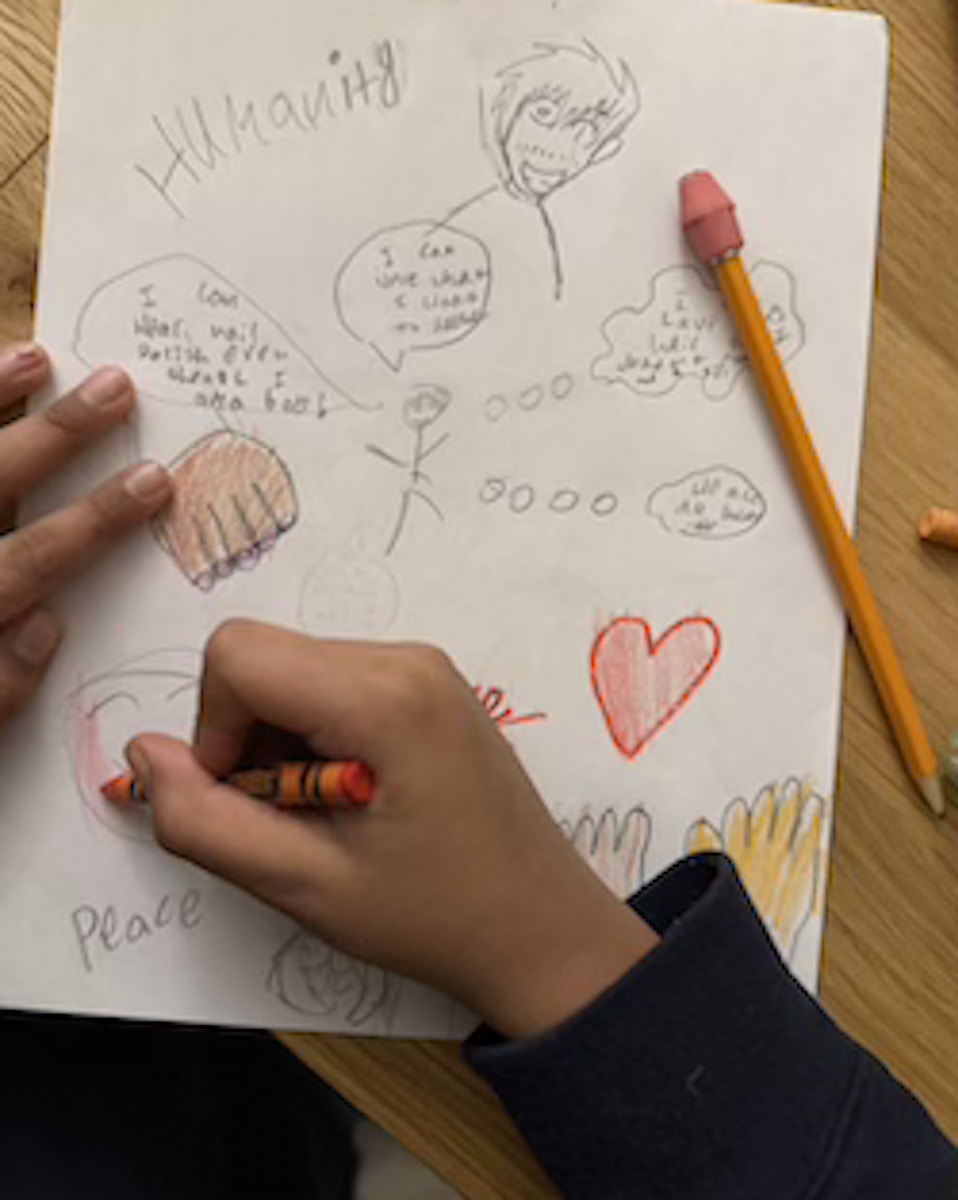

My kids are learning the same way—not through lectures, but through proximity. During the pandemic, they watched me organize with neighbors, food being shared, families lining up for help, and communities showing up for one another under pressure. After Hurricane Ida, they noticed kids their age who had lost everything and asked what we could do. None of this feels abstract to them, because it isn't abstract here.

For my sons, leaders who look like them feel normal—something I didn’t experience much as a child growing up in Queens. But they're also beginning to notice the backlash that often meets South Asian, Muslim, and immigrant representation. They're learning pride and belonging, alongside an early understanding of what representation can provoke in America.

Growing up, I sometimes felt like I didn't have the space to question beliefs my parents held. They would share their experiences and perspectives, and the expectation was that I would believe it or feel that way too. It wasn't until I was older that I started doing my own research, asking my own questions, and developing my own understanding. Now, as an adult, my relationship with my parents is different and I feel comfortable pushing back or challenging assumptions. But I had to intentionally seek out and develop those skills later in life.

I want to equip my kids with these skills from the outset. There's a difference between expecting your kids to mirror your beliefs, and having conversations about those beliefs. I want to create a space where my kids and I can talk about what I believe and give them the moral clarity and tools to build their own framework for what to believe and why. Not just to absorb what I think, but to develop the capacity to question, treason, and decide for themselves.

But let me be clear: this doesn’t mean that I'm not teaching them that everything is subjective, or that all perspectives are equally valid. Some things are simply wrong. When we see a child like Liam Ramos taken away from his family and used as bait and is unbelievably wrong. There's no gray area there. My job isn't to present that as one opinion among many. My job is to help my kids understand why it's wrong, to feel the weight of that injustice, and to think about what we do when we witness harm.

"Let me be clear: this doesn’t mean that I'm not teaching them that everything is subjective, or that all perspectives are equally valid. Some things are simply wrong. When we see a child like Liam Ramos taken away from his family and used as bait and is unbelievably wrong. There's no gray area there"

Over time, I've landed on a simple framework for how I talk to my kids about politics. First, I listen. I don't rush to correct them or shut questions down, even when the questions are uncomfortable or incomplete. I want them to know their curiosity and their confusion are safe. When my son asked about the attack ads, my first instinct was to explain.

I paused and asked him what he noticed first. He said, "They keep saying he’s bad but he’s just trying to help people." That told me everything about what he was actually picking up on—not policy, but othering. If I'd jumped straight to my explanation, I would have missed what he was really asking.

Second, I'm honest about what's happening. I explain things in age-appropriate ways and name what I believe is right and wrong, but I don't hand them conclusions. We talk about fairness, harm, responsibility, and how to decide what aligns with our values.

When they overheard the NPR segment about ICE, my seven-year-old asked, "Why would they hurt someone who didn't do anything wrong?" I didn't sugarcoat it. I told him that sometimes people in power make choices that hurt people, especially people who don't look like them or who they think don't belong. Then I asked, "Do you think that's fair?" He said no. "Why not?" I asked. And we went from there.

I'm not trying to make them adopt my politics. I'm trying to help them develop a moral framework that asks: Who is being harmed? Who has power? What does fairness look like? Those questions apply whether we're talking about a playground conflict or immigration policy.

Third, I show up with them. I take my kids to hear from community leaders and activists. I want them to see that civic engagement isn't just voting but it’s also about showing up for your community in all kinds of ways. I want them to see that protest is one way people defend their communities and care for one another.

When they overheard the NPR segment about ICE, my seven-year-old asked, "Why would they hurt someone who didn't do anything wrong?" I didn't sugarcoat it. I told him that sometimes people in power make choices that hurt people, especially people who don't look like them or who they think don't belong. Then I asked, "Do you think that's fair?" He said no. "Why not?" I asked. And we went from there.

I'm not trying to make them adopt my politics. I'm trying to help them develop a moral framework that asks: Who is being harmed? Who has power? What does fairness look like? Those questions apply whether we're talking about a playground conflict or immigration policy.

Third, I show up with them. I take my kids to hear from community leaders and activists. I want them to see that civic engagement isn't just voting but it’s also about showing up for your community in all kinds of ways. I want them to see that protest is one way people defend their communities and care for one another.

"I'm trying to help them develop a moral framework that asks: Who is being harmed? Who has power? What does fairness look like? Those questions apply whether we're talking about a playground conflict or immigration policy."

My eldest son was born in the midst of the chaos of Trump's first election and administration. He attended his first protest in January 2017, during the Women's March and many others since then. From early on, it's been important to me to take my kids along to things that matter not to instruct them, but to let them witness the world around them and the way I move through it. Panels, community events, volunteering. I wanted them to see civic life as something lived, not something abstract. Engagement becomes something witnessed, not just explained.

If showing up in person isn’t possible, contact your local elected officials by phone or email. Talking to your kids about how, on many protest days, there are also other ways to express solidarity, like choosing not to spend money.

You can also write positive messages for protesters on the sidewalk, or support local organizers who are putting together snack bags and whistle bags—many are looking for volunteers. I’ve also taken my kids to volunteer with local organizations, helping distribute essential items to families in need.

"I wanted them to see civic life as something lived, not something abstract. Engagement becomes something witnessed, not just explained."

If we don't talk to our kids about politics, they'll still absorb political messages—from ads, from overheard conversations, and from what they see online. The question is whether we'll help them make sense of what they're seeing, or whether we'll leave them to sort through it alone.

For kids of color, immigrant kids, Muslim kids, the stakes are even higher. Politics isn't abstract for them. It shapes whether they feel safe in their own country, whether they see themselves represented, whether they believe they belong. If we don't give them the tools to understand power and navigate backlash, they'll internalize the idea that these things just happen to them, rather than understanding they can participate in shaping what happens next.

We can't shield our kids from the reality that some people will question their belonging, their worthiness, their safety. But we can give them the tools to stand firm in who they are and to fight for their communities.

A few weeks ago, I saw how much this modeling matters. My older son came home with a school assignment about courage. On his own, he looked up my City Council run and wrote about how I continued doing community work even after losing. I didn't tell him to write about me. He was watching all along.

That moment reminded me that our kids' values don't come from what we say—they come from what they see. We're raising children in a time when political messaging is everywhere, when representation is both visible and contested, and when fear travels fast. We can't shield our kids from that reality. But we can give them tools to navigate it.

Our kids are watching how we move through the world—at the voting booth, in how we talk about our neighbors, in what we do when we see injustice. They're forming their understanding of power, fairness, and belonging right now, whether we guide that process or not.

The question isn't whether to talk to our kids about politics. They're already absorbing political messages. The question is whether we'll help them make sense of what they're seeing and whether we'll model the courage to stand up for our communities while teaching them to think for themselves.

Our kids deserve both: the tools to think critically and the foundation to know that some things—dignity, justice, belonging—are worth fighting for. Teaching them how to think matters more than telling them what to think. But teaching them what to stand for matters just as much.

Deepti Sharma is a serial entrepreneur, community builder, and mom of two who believes in building businesses with care and intention. A daughter of immigrants, she’s spent her career creating opportunities for women, immigrants, and small business owners.

She founded FoodtoEat, a mission-driven company connecting women- and minority-owned food businesses to corporate catering opportunities. During the pandemic, Deepti helped feed over half a million New Yorkers—work that ultimately led her to run for New York City Council.

Today, Deepti consults with early-stage founders and nonprofits, teaches entrepreneurship, and writes and speaks about purpose-driven work, motherhood, and building with community in mind. She lives in Queens with her husband and two sons and continues to build a life rooted in justice, possibility, and joy.