Getting Sticky With Josie Duffy Rice

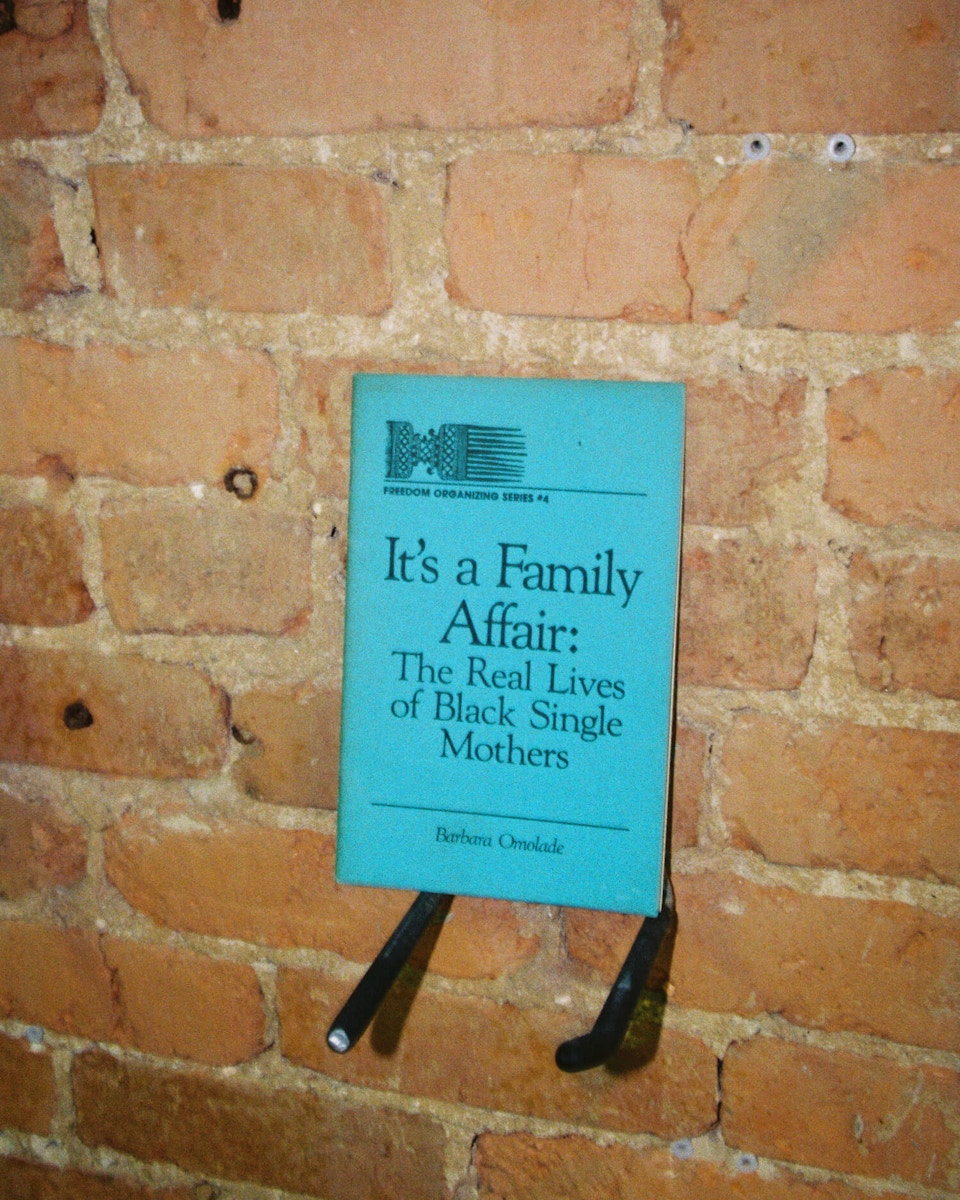

Photos by Diwang Valdez at For Keeps Books, Words by Emily Barasch

The term “public intellectual” conjures something from a by-gone era—leather-bound books, cigarette-smoke filled parlors, and Ivy Towers. But there are a handful of millennials, through the written word or into our AirPods, who deftly shape the way we think about politics, justice, and current affairs.

Josie Duffy Rice, journalist, writer, and podcast host, is one such voice whose moral clarity, critical wisdom, and sharp intellect punctures through the noise and nonsense of the current media environment. Her work mainly focuses on prosecutors, prisons, and other criminal justice issues, with writing published in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, and The New Yorker, and Peabody-nominated podcasts. Oh did we mention, she’s hauntingly gorgeous, quick to a silly joke or self-deprecating comment, and a font of parenting wisdom?

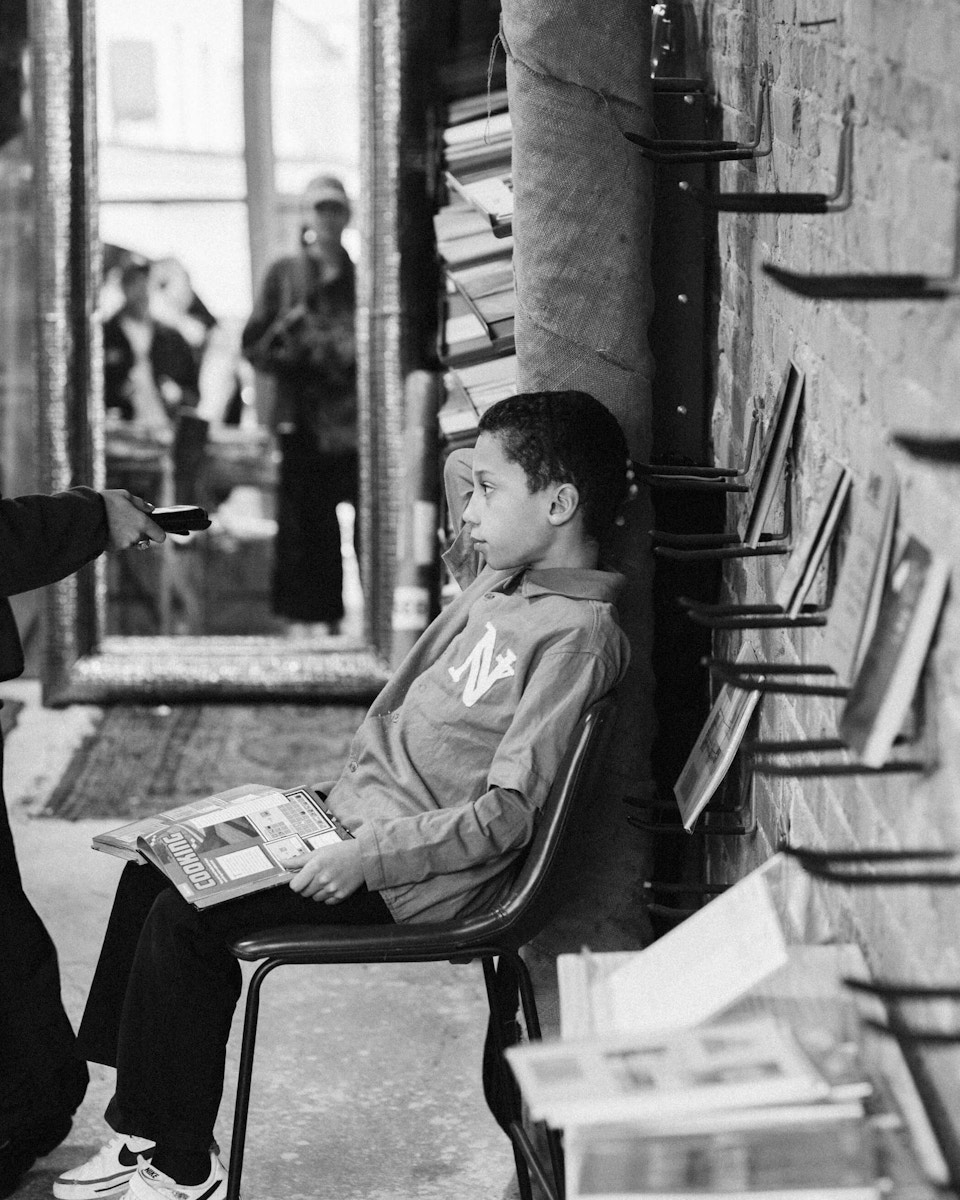

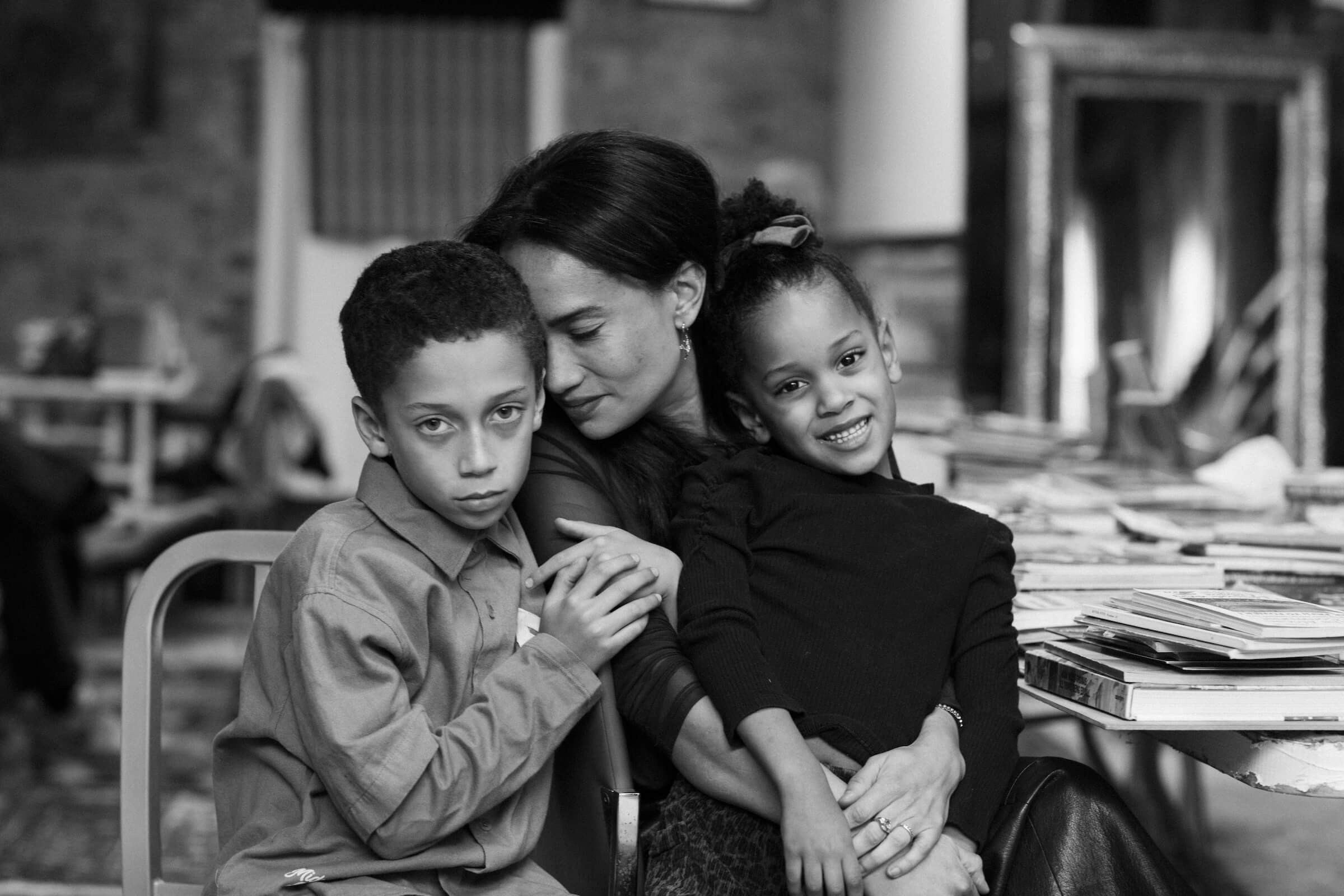

Born, bred, and currently residing in Atlanta, Josie lives with her husband Zak Cheney-Rice, a columnist at New York magazine, and two children, eight-year-old Niko and five-year-old Josie (who goes by Rami). Below, she talks about the unknowability of parenting, finding the humanity in anyone, and how becoming a mom changed her journalism practice.

I'm the fifth Josie, my daughter is the sixth Josie, and there are four of us alive right now. So my grandmother [pioneering civil rights activist and Freedom Fighter, Dr. Josie Johnson] is 95. My aunt, my mom's sister, is in her 60s, then there's me and my daughter. My great-grandmother was also named Josie and then her aunt was also named Josie. One a generation, the first one was born in 1883 and now the most recent one born in 2020.

I've always had an ambivalent relationship with my name because as a kid, it didn't really feel like mine. It felt like all these other people's names. Josie is kind of in as a name now, but as a kid, it felt so old.

I found it almost annoying. "Every time you go to anything with family, you say my name and 20 people come running like you know." But it did two things for me. One is that it kept me in line a little bit. [The message was] don't embarrass us. You're the fifth one. Don't mess it up. That was helpful. It made me a little bit more careful about doing dumb things that I'm not naturally careful about. I'm grateful for that.

It also imparted a sense of history and obligation in me. The only way I don't feel super depressed all the time is knowing that people [in my family] have gone through hard times, and that we’ll go through hard times again. You're in a long lineage and people fought for you to get here. You have to work hard. You have to. Not just to make the people around you proud, but as a return for what others have done for you. I'm trying to do the same thing for my daughter without making her feel like she can't pave her own way. I guess we'll see how she feels growing up with the same name.

"I don't know what the right level is to engage children with where we are right now. I want to say: You don't understand this, but it didn't feel like this 10 years ago. It didn't feel like this 15 years ago. How do you convey that to kids without destroying their childhood?"

“We need to be in a red state.”

In general, I really like Atlanta. My kids have a backyard and they go to a really diverse school and they are around their grandparents and their aunt. My brother-in-law also moved down here so they have a lot of family around. But then the other thing is Atlanta is in Georgia. Georgia is pretty hostile territory right now and that is something I'm trying to navigate. We've talked about moving to LA because that's where my husband's from. But LA is a gazillion dollars. It's a nightmare. You have to drive everywhere and I hate driving. It would be labor intensive in that particular way, but you'd also be growing up in a broader environment that respected the things that we care about.

Here in Georgia, there is this increasing radicalization on the right, and it feels like it's getting worse by the day. I think: I don't know if I want them growing up in a place where you go a few miles out where I literally saw two “America First” bumper stickers the other day. This is a nightmare.

There is something really important about having to navigate that because it’s not going anywhere. How do you teach kids to be around people who have abhorrent views? There's something about being in a red state where I'm like, we need to be in a red state.

The world is getting worse by the day and we're not going to win unless we, for lack of a better word, “invade” the places where the people are the most radicalized. But on the other hand, do you want to spend your life around people that hate you? And even if you're not directly around them, they're still in the ether, right? Again, Atlanta itself is great. And in many ways Georgia is great, and the South is great. It gets a bad rap, but so much about the South is amazing. But I’m also aware of the ways that it’s not.

So, I don't know. Initially we thought: It's affordable. We have family here. We'll stay for a little bit. We'll see what we think. That was eight years ago. I thought we'd leave after five years. But it's working enough that we haven't left yet.

"Sometimes I think: What a cool job to get to tell stories and talk to people for a living. Like you can't really ask for much more than that. "

How to approach this moment with your kids

I'm always navigating this question of how do I impart my kids with care and sympathy without making them terrified of the world. I want to avoid making them think that there's evil lurking everywhere because I personally don't really believe that.

I wonder: Should I be telling them more? Should I be telling them less? How do you impart curiosity about other people's hardship? I don't know what the right level is to engage children with where we are right now. I want to say: You don't understand this, but it didn't feel like this 10 years ago. It didn't feel like this 15 years ago.

How do you convey that to kids without destroying their childhood? Or maybe not destroying it, but affecting it. When I was a kid, my parents constantly talked about the the hardships of being Black in America, talked about what their parents had seen, talked about how at any given point someone could take this from you, not in a ‘you should fight back way,’ but in a ‘you don't know how lucky you are, look at all of this stuff that people had to go through to get you here’ way. That was really formative for me, and also meant I was perpetually in a state of fear about the potential harm that could befall the people I love.

At the end of the day, we’re all human

I’ve always been interested in what drives people to cause harm, especially after I graduated from college and went to the public defenders office. You're taught this flat image of people, that they're good or they're bad, they're sociopaths or they're empathetic. And then you see real people who have done horrible things and they're still people. They still hold the door open for you. They still love their kids. That drove my curiosity a lot because it felt like a solvable problem. Not that we could get rid of harm entirely, but it felt like I had grown up with this image that bad people were just bad and there wasn't much you could do about it. And the truth is almost scarier, which was that people did not have to make these decisions. Maybe there was a moment where they could have gone this way or that way. How do we prevent more people from causing harm? How do we make it so that we don't have men killing their spouses multiple times a day in this country? That really drove my interest in criminal justice.

On writing and reporting

I always liked writing as a kid and it was kind of the only thing I could do, to be honest. I wasn't good at science. I wasn't an athlete. I like to write and I like to read. Sometimes I think: What a cool job to get to tell stories and talk to people for a living. Like you can't really ask for much more than that.

[Becoming a mom] has changed my approach to journalism because I'm not likely to do as many stupid things as I used to do. I used to be a lot more combative and take more risks. I used to knock on people's doors and be more antagonistic. That's something I wouldn't do in the same way now, at least not without thinking it through. I'm responsible for more people.

For anything…

I found early motherhood to be so incredibly scary and isolating and also boring, that weird thing where you're both stressed out all the time and your brain isn't really being challenged or working. And so my mom always says this to us: "I miss when you guys were little and I wouldn't go back for anything.” And I feel like that. I watch these old videos of them and see old pictures. I'm like, "You are so cute. I wish I could have appreciated it more or had more time." But if you ask me, every year gets better and it;s gotten easier for me to develop my identity away from them, too.

Blind leading the blind

We have been really intentional in doing and trying to maintain to our children that they're not the center of the universe. We are trying to show them that they are the most important thing to us, but not the only important thing to us. The thing that I find really hard about parenting is that you don't know if you're doing it right. You don't really know what your kid's going to say in 20 years. Like you did X and in hindsight and wish it had been more like Y, or that they needed this and you didn't give it to them and that led them to have these issues. You just don't know.

You're flying by the seat of your pants with these humans that are the most important thing and you're responsible for. That keeps me up at night. Last night we had told our son he could read two chapters of his book. But he wasn't listening and we told him, since we have to ask you things two or three more times, now you can only read one chapter. He was despondent, heartbroken, and I stood by it, but then later I thought: Was I overreacting? Was I underreacting? Should I have told him no chapters? You just don't know what you're doing. You have no idea. You sort of get this impression that once you have kids, you'll just know and you don't.

"Mothering is really amazing, especially given what the world is like right now. To see people feel unencumbered joy over things and to feel like themselves. My kids are not really at the age yet where they're too self-conscious or they want to be cool. They're just fully themselves."

Power in #’s

I have a group of three close friends from high school who live in Atlanta and they also have young kids. And one of my best friends and I, our first kids are six weeks apart and my youngest and her middle kid are 10 days apart. They've been an incredible sounding board in the oh my god, I'm so fucking annoyed with my kids today. They won't listen, but also here's what happened. What would you guys do? kind of way. It is really helpful because we parent similarly. We are proponents of community discipline. If you see my kid doing something that they shouldn't do, tell them to stop. I would not describe us as gentle parents in the way that that term has been used. That has been a lifesaver because I get feedback.

When you have friends who do not approach parenting like you, it can be hard to parent around them. It's hard to figure out how to do things your way without seeming like you're accidentally insulting their way. It's hard to give advice. So I'm especially grateful for my high school friends overall, but I'm so grateful that they parent similarly to me because I'd feel a lot more isolated if that wasn't the case.

Unfettered joy > everything else

Mothering is really amazing, especially given what the world is like right now. To see people feel unencumbered joy over things and to feel like themselves. My kids are not really at the age yet where they're too self-conscious or they want to be cool.

They're just fully themselves. It is such a beautiful, amazing thing. I was in Michigan a couple weeks ago, doing this story, and I spent a day in prison and you're talking to people who are just going through this terrible, tragic stuff and then at night you call your kids and my daughter tells me, “I can write the letter H!” Thank God for that because otherwise I just don't think I'd ever step outside of it. That is the best part for me. It's amazing. You create people. It's such a wild concept when you think about it.

On the current moment

I'm having a really hard time navigating how to talk to my children about ICE, in particular. Because I want them to understand the horror of kids like them, who are loved by parents like us, being kidnapped off the street and put in prisons. We call them detention facilities, but that's an evasive word for prison. I want my children to understand that in this very real way, it could be them. But, again, I don't want to scare them constantly. I don't want to make them miserable. But I do want them to understand the role that luck plays in our lives. Because when it comes down to it, my kids have never felt the fear so many other children have to live with.

And you know, even if something terrible happened—if something were to happen to me and my husband, God forbid, my kids have an enormous family. They have grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins. They have family who would show up for them. God willing they will have someone to lean on when times get tough. I had that, too. And it's a gift I don't take for granted. Because for many people—including, but not limited to, immigrants in America—they don't have that. They're navigating unfamiliar territory in a country that is actively hostile to them, and meanwhile they can't see their parents or children for years at a time.

The other thing I want my kids to take from this moment, though, is the importance of community. I keep thinking about what Jelani Cobb said recently, that “In a democracy, the fundamental civic unit is neighbor." And I look at Minnesota, which has sparked in me both enormous dread and hope these past few months. Because obviously it shows you what a terror campaign from our government can look like. But it also reminds us that community shows up. And that defending not just your family but your neighbor's family—and I use neighbor broadly here—is in many ways the most brave thing any one person can do, and, when done together, one of the most effective.